We have learned in research that modeling and practicing social skills, including the fine art of communication, increases the likelihood of social success.¹ ² Teaching the “fine art” of verbalizing feelings is multilayered! First we have to identify emotions, then we have to identify feelings in ourselves, then we have to identify feelings in others, then we have to manage our emotions, and only then can we productively verbalize those feelings. This is hard to do at all, and takes practice to do well! We have finally reached that stage in our Casey’s training.

This is an important stage in parent training as well. Parents need to know how to listen and empathize. Most parents encourage their children to verbalize their feelings, and yet when they do, they often discover that their children are expressing displeasure over their parent’s directions! Parents may react by shutting their kids down as being argumentative or disrespectful. This pattern can impair the communication between parent and child. It’s important instead to be a “safe” person for your children; offer compassion and understanding even when you won’t change your stance.

Identifying ways in which you can reply compassionately, even in challenging situations, will encourage your child to reach out and share. As we will discuss in detail later, one can be compassionate without agreeing! When a child is angry over doing their homework, many parents will say, “Well, you gotta do it anyway, so stop complaining and get to it!” But a statement like, “I understand your reluctance to do homework. It’s difficult and I’m sure at times frustrating,” empathizes with the struggle. We may find that we don’t have to come up with a solution. Your child most likely knows what they have to do.

Being a “safe” person for your child means being a good listener and respecting their thoughts and feelings. How does a parent do this when they are also trying to instruct and direct their children through the essentials of every day life? If a parent stopped to listen to every feeling they might get caught in argument and negotiation ad nausea and very little would be accomplished.

We want our kids to express their feelings. When they talk about what happened at school or with a friend, extending our empathy is easy, and they may welcome the support. But when our children express their distress or dislike over our parenting or direction, we may feel that it just sounds like arguing, and be tempted to respond with more direction, or worse, with anger. Challenging as it can be, this is the ideal time to focus on empathy and support.

Note that even when parents can empathize with their children’s feelings regarding tasks, chores, and the ‘to-do’ list, this empathy generally should not change their direction. A child might use their new verbalizing feelings skills and say, “I feel sad when you tell me to go to bed because I’m not done playing.” But a child’s sadness doesn’t mean he’s not going to go to bed. So a parent might say, “I understand that you feel sad. It’s sometimes hard to stop playing. Let’s talk about it while we get you ready for bed.” The empathy doesn’t need to change the task at hand.

Empathizing while staying firm can look different depending on the situation. Parents need to express empathy differently during structured task time, open negotiation time, and spontaneous time.

Structured task time is the time spent in the routines of the morning, after school, or evening. It’s homework time or chore time. These are structures that you’ve put in place and are a known element in your day. These structures, much like how teachers structure a school day, set expectations and create a feeling of comfort and safety around the known. It’s best to keep these consistent and to hold to the expectations and timelines so that every second of your day isn’t open for negotiation. Again, one can empathize that a task is difficult or boring, but this understanding doesn’t change the task nor the need to get it done.

Open negotiation time is the times spent in structured family meetings when kids can safely have a say in what is happening in the family. During open negotiation, you can empathize with your child and be open to your children’s solutions and ideas. This does not mean that you will necessarily change the structure, but if your child can make a good argument for a new bedtime, let’s say, then it’s worth considering it. This will help encourage well-thought-out problem-solving and compromising skills.

Spontaneous time is all the other moments when your child talks about his feelings. Some of these moments are precious, and you need to be able to identify them as golden moments that you experience fully. One way to aid you through these moments is what we call a Support Request. When your child really starts sharing, resist making assumptions about what she needs. Instead, check in to find out what she really needs from you!

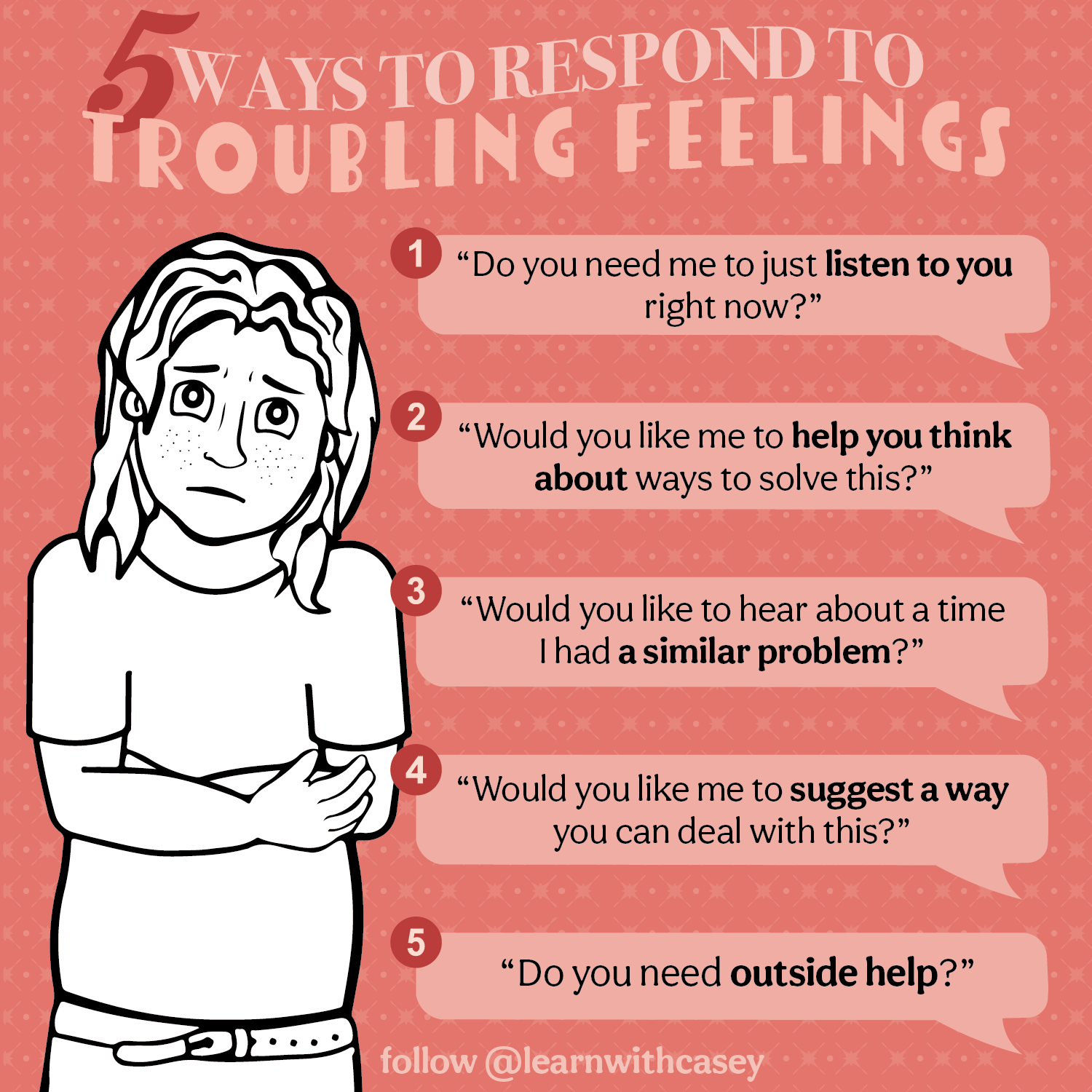

Typically, someone who is sharing troubling emotions may need you to do one (or more) of the following:

• Just Listen

• Brainstorm ideas

• Share a similar experience

• Give them advice about what to do

• Help them get help.

This is an important stage in parent training as well. Parents need to know how to listen and empathize. Most parents encourage their children to verbalize their feelings, and yet when they do, they often discover that their children are expressing displeasure over their parent’s directions! Parents may react by shutting their kids down as being argumentative or disrespectful. This pattern can impair the communication between parent and child. It’s important instead to be a “safe” person for your children; offer compassion and understanding even when you won’t change your stance.

Identifying ways in which you can reply compassionately, even in challenging situations, will encourage your child to reach out and share. As we will discuss in detail later, one can be compassionate without agreeing! When a child is angry over doing their homework, many parents will say, “Well, you gotta do it anyway, so stop complaining and get to it!” But a statement like, “I understand your reluctance to do homework. It’s difficult and I’m sure at times frustrating,” empathizes with the struggle. We may find that we don’t have to come up with a solution. Your child most likely knows what they have to do.

Being a “safe” person for your child means being a good listener and respecting their thoughts and feelings. How does a parent do this when they are also trying to instruct and direct their children through the essentials of every day life? If a parent stopped to listen to every feeling they might get caught in argument and negotiation ad nausea and very little would be accomplished.

We want our kids to express their feelings. When they talk about what happened at school or with a friend, extending our empathy is easy, and they may welcome the support. But when our children express their distress or dislike over our parenting or direction, we may feel that it just sounds like arguing, and be tempted to respond with more direction, or worse, with anger. Challenging as it can be, this is the ideal time to focus on empathy and support.

Note that even when parents can empathize with their children’s feelings regarding tasks, chores, and the ‘to-do’ list, this empathy generally should not change their direction. A child might use their new verbalizing feelings skills and say, “I feel sad when you tell me to go to bed because I’m not done playing.” But a child’s sadness doesn’t mean he’s not going to go to bed. So a parent might say, “I understand that you feel sad. It’s sometimes hard to stop playing. Let’s talk about it while we get you ready for bed.” The empathy doesn’t need to change the task at hand.

Empathizing while staying firm can look different depending on the situation. Parents need to express empathy differently during structured task time, open negotiation time, and spontaneous time.

Structured task time is the time spent in the routines of the morning, after school, or evening. It’s homework time or chore time. These are structures that you’ve put in place and are a known element in your day. These structures, much like how teachers structure a school day, set expectations and create a feeling of comfort and safety around the known. It’s best to keep these consistent and to hold to the expectations and timelines so that every second of your day isn’t open for negotiation. Again, one can empathize that a task is difficult or boring, but this understanding doesn’t change the task nor the need to get it done.

Open negotiation time is the times spent in structured family meetings when kids can safely have a say in what is happening in the family. During open negotiation, you can empathize with your child and be open to your children’s solutions and ideas. This does not mean that you will necessarily change the structure, but if your child can make a good argument for a new bedtime, let’s say, then it’s worth considering it. This will help encourage well-thought-out problem-solving and compromising skills.

Spontaneous time is all the other moments when your child talks about his feelings. Some of these moments are precious, and you need to be able to identify them as golden moments that you experience fully. One way to aid you through these moments is what we call a Support Request. When your child really starts sharing, resist making assumptions about what she needs. Instead, check in to find out what she really needs from you!

Typically, someone who is sharing troubling emotions may need you to do one (or more) of the following:

• Just Listen

• Brainstorm ideas

• Share a similar experience

• Give them advice about what to do

• Help them get help.