Laura Schneider, LMHC

Parenting | Upstanding

In order for us to talk about Upstanding, which is the act of standing up for someone who is being excluded, teased, or bullied, we need to discuss the definition of bullying so we don’t roll every mean behavior into that term.

In our Casey's Clubhouse curriculum, we introduced our 4-Square Problem/Solution Matrix. The reason I developed this matrix was because we needed to differentiate hurtful acts that children could handle, from mean and harassing behaviors that often need the help of an adult.

When I was a child, the attitude about bullying was a little different. One survived bullying. It… made you stronger. But we now know that is not true. Victims of bullying have lasting scars, and frankly, so do many of the children observing as well as doing the bullying¹.

So the days of taking it on the chin or innocently standing by are gone. We all need to act when we see unjust behavior. Obviously there are some exceptions and circumstances where our physical safety may limit our actions; however, when teaching children how to stand up for others, we need to agree that most situations are physically safe.

The bigger challenge for children is the psychological confidence to be an Upstander.

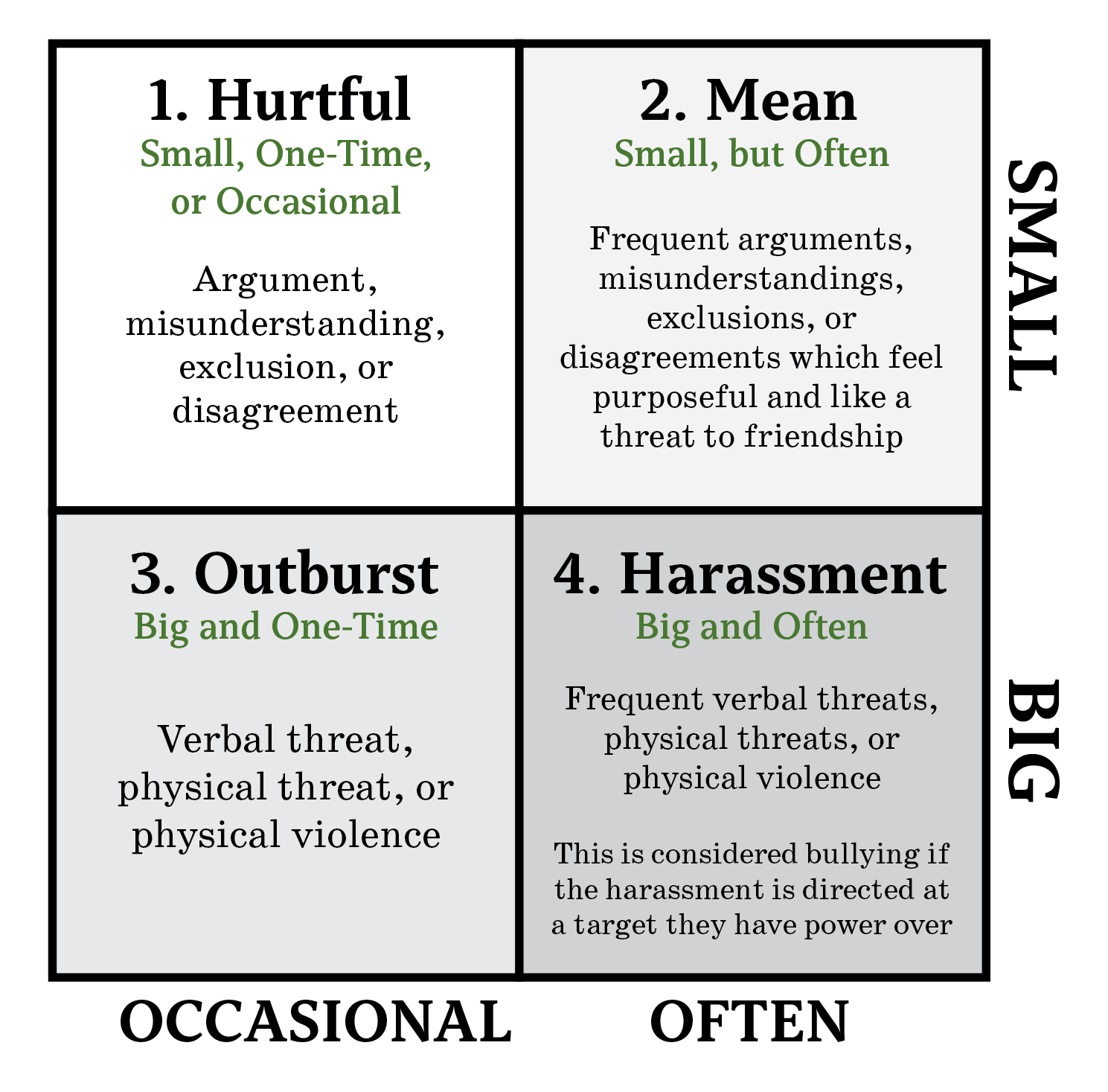

So if we go back to our 4-Square Problems, we have:

In our Casey's Clubhouse curriculum, we introduced our 4-Square Problem/Solution Matrix. The reason I developed this matrix was because we needed to differentiate hurtful acts that children could handle, from mean and harassing behaviors that often need the help of an adult.

When I was a child, the attitude about bullying was a little different. One survived bullying. It… made you stronger. But we now know that is not true. Victims of bullying have lasting scars, and frankly, so do many of the children observing as well as doing the bullying¹.

So the days of taking it on the chin or innocently standing by are gone. We all need to act when we see unjust behavior. Obviously there are some exceptions and circumstances where our physical safety may limit our actions; however, when teaching children how to stand up for others, we need to agree that most situations are physically safe.

The bigger challenge for children is the psychological confidence to be an Upstander.

So if we go back to our 4-Square Problems, we have:

- Square 1, Hurtful Acts: an occasional conflict that, with the right skill, children can handle;

- Square 2, Mean Behavior: a repeated, targeted conflict that although is not physically threatening, can be emotionally or socially threatening;

- Square 3, Outbursts: a physical expression of frustration that although not targeted, puts other children at risk;

Square 4, Harassment: a targeted, power-imbalanced, threatening, and repeated act that isolates, bullies, and controls others.

I encourage parents to be cautious when responding to Square 1 and 3.

Hurtful Acts—Square 1—is the most common. In this category, parents need to make sure they don’t misread and overreact when children are having conflict. Depending on the age and stage of your child, they can probably come up with a few effective solutions all on their own. If your child doesn’t have the skills to handle these common problems, then it’s time for them to learn from our 4-Square Solutions.

Outbursts—Square 3—aren't super common, but when a child has an outburst and your child is the unintended target, it’s easy to get upset. A child might throw something out of anger and the object hits your child. They might be playing a game and get frustrated and scream at your child, “You’re dumb!” Remember that these are children, and if your child hasn’t had a negative interaction with this child in the past, then the problem isn’t a social issue. It’s an emotional one. Make sure your school is dealing with the safety concern professionally, and help your child through the experience of, potentially, a scary moment.

The main “bully” moments happen in Square 2 and 4. Bullying happens when there is a target, a power-imbalance, and a threat. In Mean Acts—Square 2—repeated mean behavior can turn into bullying. It often starts as small acts, like teasing or name calling. Most parents and professionals leave it up to the children to work it out, just like in Hurtful Acts.

Unfortunately, sometimes these acts turn into real bullying. A child might not be physically threatened, but they are emotionally and socially compromised. Even though these acts seem petty, the repeated actions without adult intervention can cause lasting effects on the targeted child.

Harassment is less common than all the other 4-Square Problems, but it is usually the most devastating. Children are targeted by someone older, bigger, and with more social status. They have been threatened and feel unsafe. The long term risks for that child rise significantly without intervention. The bullying has to stop. Depending on the age and stage of the child bullying, there are key factors that will help stop the behavior. One of the most effective is Upstanding from their peers.

Upstanding, as we mentioned before, is the direct act of standing up for a more vulnerable person, the disruption or distraction of the unfair treatment of another, or the distribution of responsibility to address the problem.

Hurtful Acts—Square 1—is the most common. In this category, parents need to make sure they don’t misread and overreact when children are having conflict. Depending on the age and stage of your child, they can probably come up with a few effective solutions all on their own. If your child doesn’t have the skills to handle these common problems, then it’s time for them to learn from our 4-Square Solutions.

Outbursts—Square 3—aren't super common, but when a child has an outburst and your child is the unintended target, it’s easy to get upset. A child might throw something out of anger and the object hits your child. They might be playing a game and get frustrated and scream at your child, “You’re dumb!” Remember that these are children, and if your child hasn’t had a negative interaction with this child in the past, then the problem isn’t a social issue. It’s an emotional one. Make sure your school is dealing with the safety concern professionally, and help your child through the experience of, potentially, a scary moment.

The main “bully” moments happen in Square 2 and 4. Bullying happens when there is a target, a power-imbalance, and a threat. In Mean Acts—Square 2—repeated mean behavior can turn into bullying. It often starts as small acts, like teasing or name calling. Most parents and professionals leave it up to the children to work it out, just like in Hurtful Acts.

Unfortunately, sometimes these acts turn into real bullying. A child might not be physically threatened, but they are emotionally and socially compromised. Even though these acts seem petty, the repeated actions without adult intervention can cause lasting effects on the targeted child.

Harassment is less common than all the other 4-Square Problems, but it is usually the most devastating. Children are targeted by someone older, bigger, and with more social status. They have been threatened and feel unsafe. The long term risks for that child rise significantly without intervention. The bullying has to stop. Depending on the age and stage of the child bullying, there are key factors that will help stop the behavior. One of the most effective is Upstanding from their peers.

Upstanding, as we mentioned before, is the direct act of standing up for a more vulnerable person, the disruption or distraction of the unfair treatment of another, or the distribution of responsibility to address the problem.

Write your awesome label here.

Write your awesome label here.

Write your awesome label here.

Write your awesome label here.

- Direct: Speak up for the vulnerable person by pointing out the unacceptable behavior, set boundaries, and either remove the target or change the environment. This could be in person or online; however, it’s important if it’s online that the target feels supported. Instead of an online argument with the aggressor, which can often make things worse, leaving the conversation with the target shows collaborative boundaries.

- Disrupt: Engage the target by asking them to join in a different activity, or distract the aggressor by asking for their attention on something else.

- Distribute: Ask other students to stand with you to address the aggressor or ask adults to manage the problem. Each of these actions, however, take skills that most children don’t have, so we have to prepare them.

Upstanding takes skills, including confidence, communication, and problem-solving. When a peer is being harassed or treated unjustly, the Upstander has to face the fear of being the next target. They need the confidence of personhood, self-reliance, and a supportive community to act on the other person's behalf. Confidence comes from action. The action of performing at a piano recital, playing well in a soccer game, and speaking up and being heard. Children learn a lot by speaking up to their parents or teachers and being heard.

Adults are the ultimate authority for children, so when they are given a voice in their own lives, they are more confident when speaking up to peers who wield age, size, or status to set the social norm. Speaking up to “power” is not about being rude or degrading the authority of adults. It’s about increasing confidence to successfully promote one’s needs in one’s life.

We see this skill play out when children and adults speak up for themselves and others in personal and professional relationships. Allowing children to express their opinions, ideas, and insights in respectful ways gives them the building blocks to navigate social situations.

When one’s home and school encourages and supports the actions of Upstanders, then more children muster the confidence they need. Upstanding also takes communication skills that children often lack. Again, children who are allowed to speak up for themselves in the home and at school have more practice forming and using their words when they don’t agree with the social conditions. Saying, “Don’t pick on her,” is just the beginning of the standing up challenge. Saying it engages the aggressor, and now there is the potential of confrontation, something that most people avoid. So it’s important that parents and schools prepare children to stand up by using roleplaying scenarios that might occur in the classroom, playground, lunchroom, after school, or online.

I remember roleplaying with my daughter when they were being harassed about their skin condition by another student in 4th grade. We sat down at the table to mirror the lunchroom scene. I repeated the line that the child said and then we focused on calm but emotionally specific responses that connected the child’s actions to the embarrassment and hurt that my child was feeling.

My daughter said something like, “I need you to stop teasing me about my skin. It’s a painful and difficult issue for me, and your teasing is hurtful and embarrassing. Will you agree to stop?” Their boundary was well-received partly because they called out the other child, appealed to her emotion, and asked for a verbal agreement to end the teasing. Children are unprepared for direct, assertive upstanding and often back down when they realize the target or peers will not accept their harassment.

Finally, Upstanding takes some problem-solving skills. The first and most important skill is to know when to get an adult. We tell our children “safety first,” and that is so true. When physical safety is an issue, adults must be alerted. We don’t want our children putting themselves in harm's way–we want them to assess the situation and know to get help. Often when bullying is happening in schools, the students know the “players.” They know who is “mean,” who riles others up, who excludes, teases, and intimidates. So they have a better picture of the physical threat and the social threat. The physical threat may be easier to avoid than a social or emotional one.

The reason children don’t always stand up is their fear of becoming the target, losing the favor of the “popular” people, or bringing the attention back to them.

The effectiveness of Upstanding seems to be about social status. A child with low social status can stand up and make a difference, but because they don’t have “followers,” their impact is unfortunately limited. The upstanding still interrupts the act of harassment, but might not have a long term effect.

Children who stand up and have a higher social status tend to change the social dynamic more permanently. They change the tone for acceptable behavior within the larger group. Upstanding is a powerful movement against emotionally, socially, and physically threatening behavior. It sets the tone for more positive interactions like inclusion, compassion, and equality.

These are values I think we would all like to instill in our children!

One of the best ways to do this is practice, practice, practice. How can we raise an empowered generation of kids who stand up to bullying? We must get everyone on board with learning the skills it takes to be an upstander—kids and adults alike.

Works Cited

¹ “Effects | The National Child Traumatic Stress Network.” The National Child Traumatic Stress Network |, https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/bullying/effects.

Copyright © 2026

https://caseys-clubhouse.learnworlds.com/bundles?bundle_id=student-add-on-membership

Send this link to your students to purchase the Discounted Student Add-On Membership.

https://caseys-clubhouse.learnworlds.com/professional-addon

Send this link to your second facilitator to purchase the free Professional Add-On Membership.

What's included in the Casey's Clubhouse Curriculum?

The curriculum is comprised of six sections of learning: Regulation, Awareness, Determination, Problem-Solving, Confidence, and Mastery.

You can either lead club members or clients through the entire 30-Week curriculum, from Regulation to Mastery, or you can choose one of our skills-building units for a 5 or 10-Week curriculum.

Not only do you get access to all 30 of our animated stories and lessons, but you'll get a selection of lesson plans and instructions, worksheets, home activities, posters, coloring pages, and more.

Our professional subscription includes everything you need for whichever application you choose--whether that's our 30-Week program, our 5-Week units, or our independent one-on-one client curriculum.

You can either lead club members or clients through the entire 30-Week curriculum, from Regulation to Mastery, or you can choose one of our skills-building units for a 5 or 10-Week curriculum.

Not only do you get access to all 30 of our animated stories and lessons, but you'll get a selection of lesson plans and instructions, worksheets, home activities, posters, coloring pages, and more.

Our professional subscription includes everything you need for whichever application you choose--whether that's our 30-Week program, our 5-Week units, or our independent one-on-one client curriculum.

What is a Student Add-On Membership?

With the purchase of a professional subscription, you will also be able to share a discounted Student Membership option with your club members, clients, or students so they can purchase and access the Casey's Clubhouse Curriculum at home through their own logins. The Student Membership Add-On is originally $101 but is discounted at $59.

What is a Student Add-On Membership?

The purchase of the School Essential Plus Classroom Subscription includes 10, 20, or 30 Student Add-On Membership codes to send to your students, so your students can access the Casey's Clubhouse Curriculum at home through their own logins.

The School Essential Classroom Subscription allows for a teacher to show the Casey's Clubhouse Curriculum to an unlimited number of students during class, and print and hand out worksheets and Homeactivities to work on at home. This Subscription does not include Student Add-On Memberships for students to access curriculum from home.

As a startup bonus, we are offering the opportunity to share a discount code to two colleagues so they can access our Professional Membership at a discount. This way, you can build a network between you and your colleagues and share experiences and tips with each other that come with using the Casey's Clubhouse curriculum.

Let's be clear:

We don't think there's anything controversial about learning empathy, or being emotionally regulated and resilient.

In fact, we think a lot of grown-ups could benefit from some social-emotional learning.

Casey's Clubhouse empowers children ages 6-12 with hearty mental health skills by providing professionals and parents with a comprehensive animated

social-emotional curriculum that teaches:

social-emotional curriculum that teaches:

-

Regulation: Developing calming skills so kids can regulate their energy, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in ways that make sense to their unique selves.

-

Awareness: Learning observational and mindfulness skills so kids can be aware of how they're feeling on the inside, and what's happening around them.

-

Determination: Identifying goals, assessing them in relation to their ability to get there, coming up with the steps, and then putting the steps into action.

-

Problem-Solving: Creating a framework to conceptualize and organize problems of varying degrees, and finding healthy solutions to those problems.

-

Confidence: Following a bill of fair, respectful, and compassionate Friendship Rights and Responsibilities to increase advocacy skills and self-worth.

-

Mastery: Feeling confident in the ability to use a skill so effectively, easily, and appropriately, that they can successfully teach another. Great for supporting our Peer Leaders.

When you become a member with us, you get:

-

30 animated stories and lessons about Casey and his friendship struggles and successes.

-

A comprehensive curriculum of lesson plans, home activities, worksheets, coloring pages, music, and more.

-

Ample resources for the grown-ups in a child's life.

-

Guaranteed assistance and customer service.

-

The amazing feeling that comes with making a difference in kid's lives, without having to reinvent the wheel to do so.

Write your awesome label here.